Defining Multiple Sclerosis

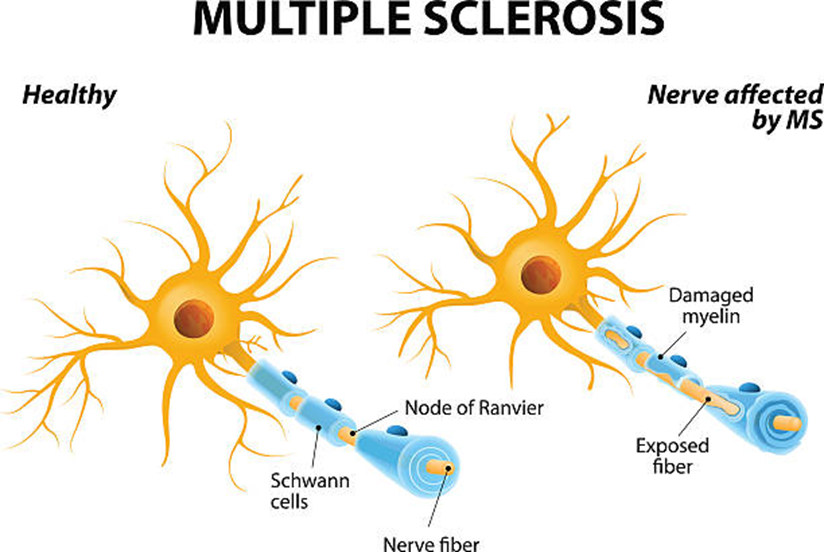

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease affecting the central nervous system. In MS, the immune system incorrectly attacks the myelin sheath, the protective covering surrounding nerve fibers, as well as the nerve fibers themselves. This damage interferes with signal transmission in the brain and spinal cord, producing an array of neurological symptoms. MS is characterized by periods of exacerbation or attacks on the myelin, followed by recovery periods of remission as inflammation subsides. There is no known cure, so treatment aims to manage symptoms and slow disease progression.

Statistics on Prevalence

Globally, over 2.5 million individuals have MS, making it a leading cause of non-traumatic disability among young adults. Women are diagnosed 3 times more frequently than men. While the disease can occur at any age, onset is typically between ages 20-40. MS rates are highest in North America and Europe though prevalence is rising worldwide. The reasons for geography and gender patterns remain unclear, signaling more research is needed on genetic, environmental, and other MS risk factors.

Common Symptoms and Signs

Given MS arises from neurological damage, symptoms manifest in diverse ways depending on the location of nerve inflammation. Most common symptoms include overwhelming fatigue, gait problems with numbness or imbalance while walking, limb numbness or tingling, chronic pain, bladder and bowel dysfunction, visual changes like blurred or double vision, weakness and immobility, muscle spasticity, cognitive changes affecting memory and concentration, and depression. Since symptoms stem from periods of inflammatory demyelination, they may resolve partially or completely during remission periods when inflammation subsides and nerves recover.

Multiple Sclerosis and Disability

In MS, neurological disability accumulates through repeated inflammatory attacks damaging nerve cells over time. The location of myelin lesions and nerves affected determine the types of symptoms that emerge such as vision loss, mobility impairment, tremors, and cognitive decline. The pace of disability progression varies widely, though approximately 15% of patients will develop significant disability within 10 years of diagnosis. Tracking progression guides treatment intensity, with early intensive therapy aimed at limiting future permanent disability.

Diagnosis and Testing

No single test can definitively diagnose MS given its complexity. Physicians synthesize findings from a neurological exam testing coordination and reflexes, patient-reported symptoms, MRI scans revealing myelin lesions and scarring in the central nervous system, and a spinal fluid analysis detecting inflammatory proteins and antibodies associated with MS immune activity. Other potential root causes are first ruled out. Updated diagnostic criteria now enable earlier, accurate diagnosis in most cases compared to the past.

Types of Multiple Sclerosis

MS is categorized into 4 main types based on the progression pattern over time after onset: Relapsing-remitting MS involves acute symptom flare-ups followed by recovery periods, and is the most common type initially. Primary progressive MS involves steadily worsening neurologic function from the beginning without any remissions. Secondary progressive MS begins with relapses and remissions then transitions into more steady progression without remissions. Progressive relapsing MS shows both a progressive disease course and acute intermittent flare-ups.

Disease-Modifying Treatments

While no cure currently exists for MS, over a dozen disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) aim to modify inappropriate immune system activity to reduce flare-ups and thereby slow the accumulation of neurological disability over time. DMTs include injectable immunomodulators, oral medications, and intravenous monoclonal antibody infusions. The number of treatment options has proliferated in just the past 15 years. Choosing an optimal DMT and closely adhering to the regimen is key for each patient to maintain strength, mobility, and quality of life.

Lifestyle Measures and Self-Care

Lifestyle adjustments and self-care practices can meaningfully augment medical treatments to better manage MS symptoms and progression. Adequate rest, appropriate exercise, proper nutrition including anti-inflammatory diets high in omega-3s and antioxidants, and good sleep hygiene all help optimize patient well-being. Learning to manage stress levels, maintain social connections, adapt living spaces for greater accessibility, and proactively ask for assistance also enables successfully navigating life with MS. Counseling often benefits emotional health.

Specialized MS Healthcare Team

Caring for MS patients is optimally achieved through an interdisciplinary healthcare team approach including neurologists closely tracking disease progression and tailoring DMT regimens accordingly, physical and occupational therapists addressing mobility limitations and adapting daily activities, psychologists monitoring and supporting emotional health, nurses training patients on self-injections and side effect management, and other specialists who can help relieve specific symptoms should they arise. Overseeing care through such an expert team promotes quality of life and patient empowerment.

Hope for the Future

The future outlook for MS patients continues getting brighter as research uncovers new understandings about the underlying disease mechanisms and brings more treatment options to market, including extremely effective and better tolerated DMTs. Active investigations into stem cell therapies, remyelination techniques to repair nerve damage, novel emerging immunotherapies, and neuroprotective compounds to slow progression are underway through clinical trials. While MS remains incurable presently, the future promises greater probabilities for slowing disability and retaining mobility and independence.