Many people are surprised to learn that smoking can increase their risk of macular degeneration. The good news is that it’s easy to lower your risk by getting regular exercise and eating a healthy diet that includes leafy green vegetables, orange and yellow fruits and veggies, and nuts.

The VIP Study and the Beaver Dam Eye Study confirmed a dose-response effect, with the risk for neovascular AMD increasing with the amount of pack-years smoked. Other studies, such as the Physicians’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study, have also found similar results.

Increased Risk of Macular Degeneration

The oldest and most reliable research to date has shown that smoking increases the risk of developing age-related macular degeneration (AMD) by at least twofold. This increased risk applies to both current and former smokers, and the more cigarettes smoked in life, the greater the risk.

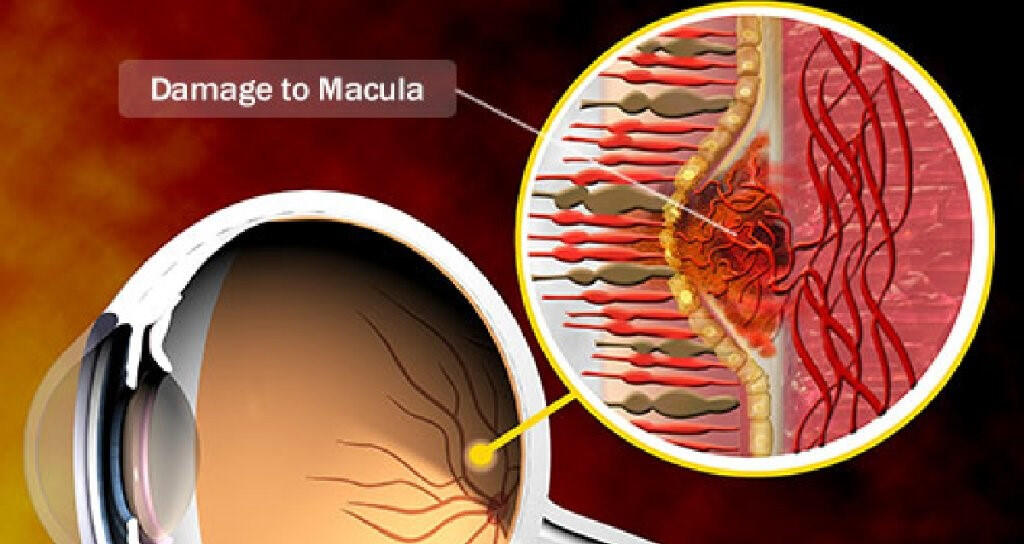

Smoking causes the tiny blood vessels that nourish the retina (the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye that helps you see fine details clearly) to constrict. This can lead to a higher incidence of both the dry and wet forms of macular degeneration, resulting in permanent vision loss.

Smoking may also affect the pigments lutein and zeaxanthin in the eye, which are important for protecting against UV radiation-related macular degeneration. Studies that examine the association between these pigments and smoking suggest that they are reduced in people who smoke, allowing damaging UV to reach deeper into the eye.

Role of Oxidative Stress

Smoking impedes the body’s natural ability to produce and recycle antioxidants, which protect cells from damage. In addition, the tar in cigarettes contributes to the formation of drusen — fatty deposits on the retina that indicate the early stages of macular degeneration.

Researchers believe that these drusen can trigger a process called oxidative stress, which leads to the development of wet macular degeneration. Wet AMD can lead to severe vision loss if it is left untreated.

Studies have shown that smokers experience a faster progression of the disease. One study found that current smokers with wet macular degeneration developed the disease 5.5 years earlier than nonsmokers.

Smoking cessation significantly reduces a person’s risk of developing AMD and slows the progression of existing disease. Recent research shows that smoking cessation may improve the outcome of laser treatment for wet macular degeneration. However, longer follow-up data are needed to confirm this observation.

Inflammation and Immune Response

Smoking is associated with a greater risk of wet macular degeneration, which leads to severe and irreversible loss of vision. While there are several risk factors for developing wet macular degeneration, including age and genetics, smoking appears to be the primary modifiable factor.

The tar in cigarettes is thought to cause the formation of drusen, which are fatty deposits that accumulate under the retina and contribute to early dry AMD. The inflammatory chemicals in cigarette smoke also stimulate the immune system to produce excessive responses that can damage tissue, including the eye.

Observational studies show that smokers have a two to four times higher risk of developing macular degeneration, including wet AMD. In addition, there is evidence that this risk may be reversible. One study found that former smokers had a much lower risk of wet AMD than those who continued to smoke, suggesting that the effect is reversible upon cessation of smoking.

Association with Wet Macular Degeneration

In the wet form of age-related macular degeneration, fluid leaks under the retina, causing straight lines to become distorted. Wet AMD can quickly lead to severe central vision loss. Treatment for wet macular degeneration is less effective than dry macular degeneration treatment, and a cure has not been found.

Ophthalmologists at UC Davis Health have recently used an experimental gene therapy in the treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration, also known as neovascular or exudative AMD. The treatment, ABBV-RGX-314, is part of an ongoing randomized, partially masked, controlled clinical trial.

Several large epidemiologic studies have associated smoking with an increased risk of developing age-related macular degeneration and eventual blindness. This new study provides a better understanding of how cigarette smoke induces the biological changes that result in macular degeneration, and it is important to emphasize the importance of preventing and quitting smoking as a way to reduce this risk.

Impact on Treatment Outcomes

Several epidemiological studies have shown an association between smoking and macular degeneration. A few of these have been extended into longitudinal studies and found to fulfill the criteria for causality.

These findings suggest that the increased risk of AMD associated with smoking may be caused by a combination of factors. Specifically, it may be related to decreased blood flow through the retina due to smoke-induced oxidative damage and reduced macular pigment density in smokers.

The study also found that long-term smokers have a compensatory increase in retinal blood flow, which can partially explain the increased prevalence of dry AMD in this group. However, the study was limited by its small sample size and short duration of follow-up.

Other independent researchers have found that current smokers are up to four times more likely to develop late AMD compared with never smokers. In addition, a joint effect of current smoking and a low level of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol or high ratio of total to HDL cholesterol, and a low fish consumption was found to be more significant than the effect of any single risk factor alone.

Smoking Cessation as a Preventive Measure

Smoking cessation is an effective preventive measure against many health problems. The benefits of smoking cessation begin within hours, with reductions in heart rate and blood carbon monoxide levels. Platelet activation and inflammation also decrease rapidly. After one year, excess coronary heart disease risk can fall to half that of an active smoker. Excess stroke risk is eliminated at about five years, and the risks for oral, throat, esophageal, and bladder cancer are substantially reduced.

A range of behavioral and pharmacologic interventions have been shown to be effective in assisting people to quit smoking. Clinical practice guidelines recommend that clinicians ask all adults about tobacco use and advise and treat those who smoke to quit. Workplace interventions and community/policy level strategies can motivate people to quit. Smokers hospitalized with cardiovascular disease are more likely to quit smoking after being given a smoking cessation intervention by their physician (78). Smoking places a substantial burden on smokers, healthcare systems, and society through the premature death it causes and increases in healthcare expenditures resulting from smoking-attributable diseases.