People with high-risk multiple myeloma face a more challenging prognosis than those with standard-risk disease. For those who are eligible for a stem cell transplant, induction therapy (including stem cell collection and stem cell storage, high-dose melphalan chemotherapy, and autologous stem cell transplantation) offers the best chance of a long-lasting response.

Risk Stratification and Staging

Although multiple myeloma survival has improved considerably over the past decade, 15-20% of patients are still considered to have high-risk features, with a predicted OS of less than three years. They may have co-occurring cytogenetic or genetic abnormalities or they have relapsed within one year after autologous stem cell transplantation (AHCT).

Several criteria for risk stratification have been proposed. The IMWG currently recommends the detection of t(4;14), t(14;16) and del (17p) in selected plasma cells by interphase fluorescent in situ hybridization as an important prognostic marker. In addition, low albumin and high b2-microglobulin levels are also associated with poorer outcomes.

Nevertheless, current risk assessment systems cannot reliably predict long-term structural recurrence because they rely on data available at initial treatment and fail to take into account response to therapy. This is why we need to focus on generating more high-quality data and develop dynamic risk stratification strategies based on the evaluation of responses to therapy.

Intensive Induction Chemotherapy

Intensive induction chemotherapy is the initial treatment for most multiple myeloma patients. This usually consists of a three- or four-drug combination regimen given over several cycles. The drugs kill cancer cells and also damage normal bone marrow. These drugs include an immunomodulatory drug (such as Revlimid or Pomalyst), a proteasome inhibitor (such as Velcade or Ninlaro), and a monoclonal antibody (such as Daratumumab or Empliciti).

In addition to these chemotherapy drugs, your doctor may use radiation therapy to prepare the body for a stem cell transplant. The type of radiation used depends on your particular situation. It can be delivered through an external radiation machine, called total-body irradiation, or through high-dose chemotherapy followed by stem cell transplantation.

Your doctor will determine if you have high-risk features and recommend a treatment strategy for you. These strategies aim to achieve a deep response, as well as minimize disease progression and improve your overall survival.

Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation

Autologous stem cell transplants involve your own bone marrow stem cells being collected and stored, then infused back into your body after intensive therapy. Using your own stem cells avoids the risk of graft-versus-host disease, where the new stem cells from a donor might attack your normal blood cells.

We start the process by giving you a few days of high dose chemotherapy and radiation therapy to destroy any remaining cancer cells and make room for the new stem cells in your bone marrow. This is called conditioning therapy.

Your doctor can also use medications to help your stem cells move out of the bone marrow into the bloodstream (called mobilization). We then remove the stem cells from your blood through a process called apheresis or bone marrow aspiration, and they are frozen and stored. After induction chemotherapy and ASCT, the stem cells are thawed and infused back into your bloodstream to rebuild your bone marrow.

Maintenance Therapy

The prognosis of people with multiple myeloma has improved considerably in recent decades, but a significant group of patients, identified by specific clinical and genetic criteria, continue to respond poorly to standard treatment. This group represents a major challenge to physicians and needs early identification and personalized management.

Maintenance therapy is a long-term medical treatment that is given to help the original primary treatment succeed and prevent relapse. It may be chemotherapy, or targeted therapy, such as bortezomib plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

The best way to determine whether or not you need maintenance therapy is through regular bone marrow samples and MRI scans. These can identify the presence of clonal plasma cells and the number of circulating myeloma stem cells. This information is useful for predicting the likelihood of relapse and choosing suitable therapy. Evidence from relapsed/refractory trials indicates that early reintroduction of active treatment significantly prolongs PFS and OS.

Immunotherapy and Monoclonal Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies are laboratory-made proteins that mimic the immune system’s ability to fight infection. They attach to antigens, which are molecules on cancer cells that the immune system recognizes as harmful, and trigger an immune response to destroy those cells. Some monoclonal antibodies mark cancer cells so that the immune system can better see them and attack them. Rituximab, for example, binds to a protein on B cells (white blood cells) and some types of cancer cells, marking them for destruction by the immune system.

Other monoclonal antibodies combine with chemotherapy drugs and deliver them directly to the cancer cell, a process called antibody-drug conjugates. Examples include trastuzumab emtansine, which combines the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab with the chemotherapy drug emtansine.

Other mAbs work directly to stimulate the immune system’s anti-tumor activity. One such approach is bispecific T cell engager (BiTE) antibodies, which combine the specific targeting of a tumor antigen with an activating receptor on the surface of T cells to bring those T cells into close proximity with cancer cells and enable them to kill them more effectively.

Clinical Trials and Emerging Therapies

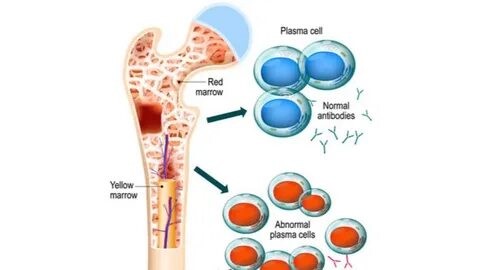

With the development of novel therapies, survival for multiple myeloma has improved significantly. However, a subgroup of patients remain at higher risk for a poor prognosis despite the use of these newer agents. They are identified by co-occurrence of high-risk features, such as extramedullary disease or cytogenetic abnormalities, or early relapse after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHCT) [Fig 1].

Stem cell transplantation replaces the disease-producing myeloma cells in the bone marrow. This can be a very effective treatment but also has significant morbidity and long-term complications.

Several clinical trials are investigating strategies that may lead to deeper responses and ultimately cures in this group of patients. These include neoadjuvant therapy (induction followed by AHCT) and combinations of agents that work in different ways (proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs and monoclonal antibodies), including the newly FDA-approved Xpovio (selinexor). Patients who are at high risk may be offered these therapies as part of a clinical trial.